Emily Kendal Frey

Sorrow Arrow

Octopus Books

reviewed by Nina Puro

I’ve been reading Emily Kendal Frey’s Sorrow Arrow since about February. It’s July.

Each poem is comprised of unpunctuated phrases that are double-spaced, un-titled, and indexed by first line. This might seem challenging, but there’s a compelling warmth: the reader is invited in, compelled to continue. Her strange world opens and opens. I understand more and more. I’m understanding Frey’s universe, which is to say our universe: how precarious and breathtaking it is to fully inhabit a consciousness and cart it through a landscape. It’s not conceptual —it’s a page-turner.

What would an experimental beach read look like? It would look like Sorrow Arrow.

I was so in love that I mapped the book because I wanted to understand how she does it (which is to say I wanted to steal her dance moves). The text loosely chronicles a romantic relationship and a trip abroad, which sounds really cute and safe. But the narrative is somewhat beside the point. The point, to me, is the generosity and perseverance in the face of difficulty.

I experience the world in a deeply somatic way, and I found myself rocking, as I sometimes do when I’m really feeling the work. Yet this time in the rocking, there was a sort of twisting in my chest: a damp sponge in my inside my sternum made of static electricity or TV fuzz being wrung out, filling slowly, being squeezed again.

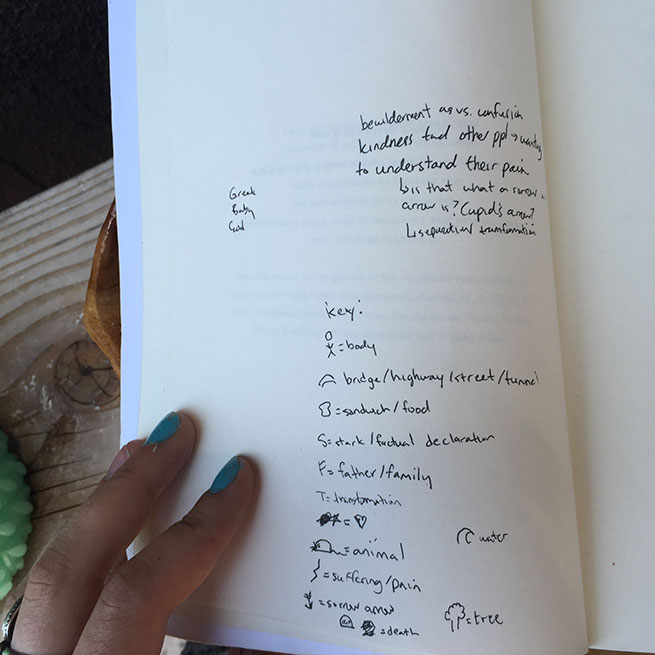

The book is rife with repetition, both conceptually and lyrically, so I mapped them with a key of pictographs on an inner page.

This is probably either the most twee thing or the most nutty thing a poet did in Brooklyn in February, or both. For what it’s worth, I did it before I knew I was going to write the review.

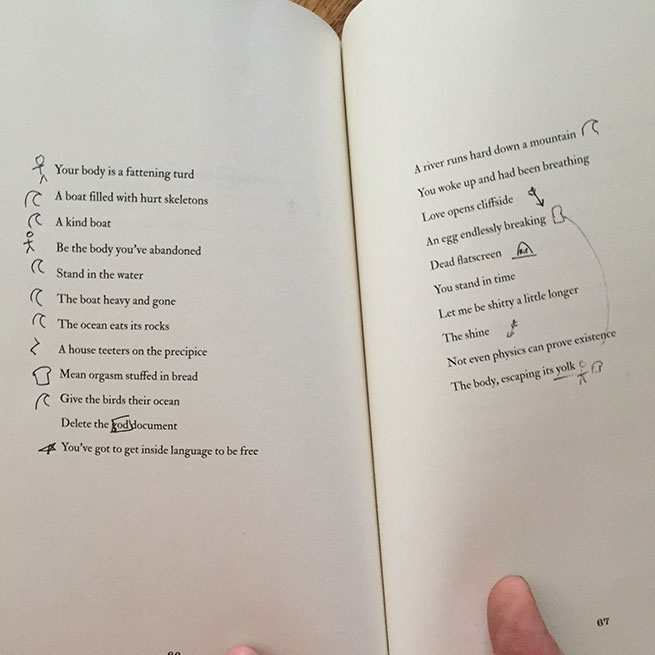

The map looked something like this:

I marked made up pictograms for: body; bridge/highway/street/ tunnel; sandwich/ food; stark/ factual declaration; father/ family; transformation; <3 (lines I particularly loved) ; animal; suffering/ pain; Sorrow Arrow; death; tree; water.

So the poems looked something like this:

There are also words that seemed to be tied to larger concepts about lineage and goals for the future, a second parallel set of concerns, somewhat like state lines on a map in which a cartographer is marking in the highway lines. I drew squares around them and sometimes linked them with arrows. They were: Greek/ myth; baby; God.

To me, a Sorrow Arrow is the key to understanding the purpose of Frey’s work in this text. The first I marked is “People are intriguing and boundaried.” The second “We’re shaking- blurry almost/ The suffering of us/ At the center of suffering is love.” (1).

It’s a desire to fully understand another person’s pain and, in doing so, reside within it. (“My arms open as soft cheese/ Milk chest/ Wolf chest I heap my limbs on/ I got so far in your pain that it rained”) (3)

Everyone knows that moment in candid conversation when someone speaking about something that is troubling them crumples or bursts into tears. To me, a Sorrow Arrow is what the non-crier feels during that moment. It’s the idea of cleave and how it can be a pulling apart or a pushing together. Cupid’s arrow, yes, but also the transformation that comes through separation. It’s kindness not just to sustain contentment, but when the goal is to fully cognize another person’s suffering: “I’m sorry I wasn’t able to get inside your color/ the sky was cobalt, deafening” (57). There’s a radical generosity in a witnessing this empathic, and Frey displays it over and over again. “I like her Chevy/ I like her not yet extinct” (77). “I climb the path/ Bloody teeth rain down/ It hurts to be born/ God are you there/ Are you standing in the shadow of my sorrow/ Yet” (86)

Part of me secretly wishes Frey was my big sister, or that I wasn’t a deeply suspicious cynic/ cold-hearted bitch, or both.

Or perhaps the longing I felt is a wish that I had a deeper wellspring from which to give: endless reserves, or that I was not so maudlin as a person.

(I can’t wait to get older.)

I should note that some part of me was wondering how Frey’s wellspring got so deep, and whether it was the product of a perceptive, sensitive mind contemplating the horrorshow landscape that is America’s sweet ruin yet personally inhabiting a home base that had mostly been more or less pleasant, featuring readily available basic resources; a surfeit of choices; and minimal recurring trauma and/or routine fear of violence. (“My childhood is full of wild strawberries” [15]) I suspected that it did. My suspicion might well be entirely inaccurate. But… Frey is straight and white and lives in Portland. So.

This is more a query than an observation, and if it was accurate it wouldn’t be a bad thing—the book is still in my top five all year.

Part of that, too, is because it made me cackle frequently. Frey’s humor is self-eviscerating and mordant.

Frey both adores the world and doesn’t shy away from addressing the darkest parts of being human, and this is an act of bravery. These are brave poems. Frey doesn’t describe the world rapturously; she allows for confusion, even bewilderment. She allows for viscera and hilarity side by side. One way she frequently does so is by marking the passing of time. In doing so, she wields both seasonal markers and the reminder of the inevitability of death. (22)(8)

Or, as Ruefle writes, “I hated childhood./I hate adulthood./ But I love being alive.”

In this, there’s a deep appreciation for family but a respect for the complexities of lineage. “In Italy my sister is eating a digestive cracker / She’s straightening her bangs / Her eyes / Her long-sleeved blue shirt / I’m sorry for the childhood we had to have / I’d like to go back / Give her a drink of water” (39) And through—because of?—this, there’s a bracing respect for everyday lived experience. This respect is particularly feminine: it delineates work that and illustrates tasks that are “mundane.”

Sometimes Frey’s mapping of hungers and consumption borders on what could be viewed as materialistic—“Kombucha tea was taken off the market” (58) “At the airport bar people are drinking clear drinks/ Their hands in cashews / The girl in gray shoes orders into the air” (47) But: we are hungry animals who move around the world shoving our maws deeper into the trough. Illustrating this is one of Frey’s talents.

“Don’t die summer / There are wolves among us / We promise to make more art” (53)

Frey’s greatest skill is perhaps her radical generosity and the control and economy she displays in her explorations. Her language is sharp and unpretentious; her humor alternately mordantly sardonic and goofy; her tone both subjective and deeply immersed within the scope a world where “we are resurrected/ at the store/ there is light/ eggs break” (73). She is able to hold both an intimate moment with another person and their larger archetypal pattern simultaneously, and in doing so, imbue the everyday with a greater significance, e.g. a historical and political weight. Sorrow Arrow both eschews and captures the complexities of being in the world and, in this, clarifies and expands what it is to be, despite that “I can see someone is failing/ A great failure might occur” (33).